In his essay 'Grace and the Word', Carl Schorske argues that the liberal ascendency in Austria, having coherently linked its distinct political, scientific, and aesthetic cultures, nevertheless came to a fractious cleaving by the end of the 19th century. It was then, as the promise of early liberalistic pursuits for rationality and rule of law began to wither under the reality of masked absolutism, that aesthetic culture turned away from the enlightenment fueled axioms found in politics and science and moved towards a baroque model rooted in counter-reformation ideals of the 17th century. The aesthetic split and turn to the baroque was not without justification. Schorske claims that the educated Austrian bourgeoisie cultivated a unique cultural aesthetic precisely because the printed-word based reformation ideals, built upon an enlightenment rationale, did not take hold in Catholic Austria as it did in Protestant dominated Northern Europe. Instead, counter-reformation ideals, built upon a baroque rationale that sought to incorporate the spiritual in art, informed the Austrian aesthetic and gave the Central European power exquisite examples of what Schorske termed the "applied and performing arts: architecture, the theatre, and music, wherein the spirit was concretely manifested."

Selecting two institutions, the theatre and the university, Schorske demonstrates how this streak of counter-reformation infused aestheticism fractured the alliance between grace and the word in Austrian elite culture. As disaffection with liberalism began to manifest around 1870 due to ethnic, social, political, and economic frustrations, this union began to loosen, then break, as the youth looked to the arts for divining meaning in their time. Once freed from rationalism, the Austrian aesthetic culture searched for a more divinely inspired source of defining the self, holding the 'instinctual' as foil to the 'rational' and in doing so "challenged and eroded the authority of liberalism as a socio-cultural value system."

Of course, without knowing it, Schorske tapped upon a conflict only now becoming vogue and more seriously investigated, that being the inherent assumptions found in dualist and augmented configurations of reality. Nathan Jurgenson, in an article titled 'When Atoms Meet Bits', outlined what is at stake in the augmented versus dualist debate, particularly regarding integration of digital technologies into our daily lives. Those that view the digital and physical to be separate epistemological realms of knowledge uphold a digital dualist perspective on reality, and believers include ranks of cyber-utopians and dystopians who see in the digital a new world:

"Indeed, digitality promised a Wild-West like frontier built without replicating the problem of our offline world; fixing the oppressive realities such as skin color, physical ability, resource scarcity, as well as time and space constraints."

Alternatively, Jurgenson advances the augmented conception in which the digital and physical are intermeshed. Occurrences and affordances of the digital impact the physical and vice-versa, and although the epistemological operations of both differ, their interactions are joined through constructed knowledge transition points, or handoffs.

"The physicality of atoms, the structure of the social world and offline identities 'interpenetrate' the online. Simultaneously, the properties of the digital world also implode into the offline, be it through the ubiquity of we-connected electronic gadgets in our world and our bodies or through the way we understand and make meaning of the world around us."

Conflict between Baroque and Enlightenment ideals in Austria, couched by Schorske as resurgence of counter-reformation influences in the face of liberal dissatisfaction, can also be seen as a conflict between dualist and augmented conceptions of reality, albeit not in digital but rather textual terms. In an age before the appearance of widespread near-instantaneous communication networks, it was the written word, personified in manuscript or print form, that provided the catalyst for dualist conceptions of reality through the tax registers, passports, and census records authorities zealously sought to collect during the modern turn in governmental reason.

Documentation, however, is only as good as the validity of the data recorded. Lived reality of subjects during the 17th-19th centuries could often radically differ from the documented projection of these populations and this fundamental asynchronicity between the document and the lived expression not only fueled creation of disciplinary societies, one subject of many explored by Foucault, but also the textual dualist conceptions of reality that went hand in hand with the rise of liberalism and rationalism as Enlightenment-centered philosophies. Schorske's essay 'Grace and the Word' should be taken to mean 'Augmented Grace and the Dualist Word', as the baroque reaction of Austrian aesthetic culture represented a turn towards augmented conceptions over those of the dualist, word based claims of the enlightened cultures of Austrian politics and science.

Understanding how the modern era is both shaped and impacted by ongoing debates between dualist and augmented conceptions, the likes of which Schorske's essay details, is no simple task. The sheer spectrum of subject matter involved- reality itself- boggles any attempt at succinct summation. Even my paltry efforts of description in the paragraph above begs more exploratory depth.

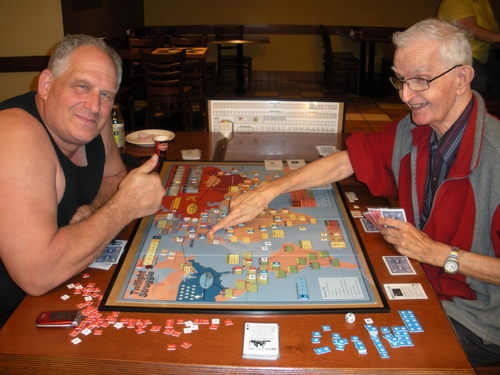

One means of reducing the scope of investigation, without sacrificing theme, would be to find a common institution or cultural construct that has roots in baroque and enlightenment ideals of the 17th century, as well as a continued, evolving form from that period and up to the present day. Surprisingly, board games fill this needed role nicely. While their origins trace back thousands of years, it was the 17th century when a shift in what playing a board game could inform, that is the epistemological boundaries of play, became intertwined with the rise of modern social, political, and governmental techniques and disciplines. Whereas previous games, like Go or Chess, produced knowledge through play, this knowledge was considered abstract and often tangential to the real world. One had to literally translate the lessons of Go to make use of its knowledge on the battlefield. As such, these early games presented a dualist version of reality, a distinct knowledge sphere related to, but separate from, the knowledge sphere of real life.

Then, in the 17th century, Ulm patrician Christoph Weickmann had the idea for his 'King's Game' which introduced a de jure possibility for board games to present an augmented reality conception, a process that hinted towards a meaningful interaction between knowledge produced through play and knowledge directly applicable to real life. From here, board games of various types would struggle, unequally, towards the production of de facto knowledge, with wargames leading the way and more socially-focused games only recently catching-up. Realization that games are de facto knowledge producers first appeared in literature, then in actual game design, with Hesse and Coover providing bookends of this realization in novel form and games like Twilight Struggle and Andean Abyss integrating this logos into their ludic expression. Implications of this analysis demonstrate a precise need for more serious studies on the design, play, and experiential aesthetics of board games in the modern period.

The first part of this essay, 'The Epistemic Reservoir', will define the terms de jure and de facto augmentation and focus on how Weickmann's visionary design proved that board games could become augmented, not just dualist, sources of ludic knowledge. However, while Weickmann's game laid the foundation for future iterations of augmented design, it also provided a field of knowledge upon which Enlightenment ideals could take hold and spread. The second portion of this essay, 'The Limits of Dualism', looks at the implication of augmented ludic knowledge for Enlightenment ideals and how these ideals suggested textual dualist discourses in all but the military spheres of life up to the 20th century. Extensive use of documentation techniques by authorities to define the self led to extreme dissatisfaction with liberal ideals that empowered documentary efforts. As dualist regimes reeled at the end of the 19th century, there was casting for a new, augmented reality and the third portion of this essay, 'The Augmented Turn', looks a how literature and board game design of the 20th-21st centuries reconceptualized the board game as a de facto augmented ludic knowledge producer.

Part I: The Epistemic Reservoir

It is no coincidence that the 17th century in European history, a period that saw the emergence of both Baroque and Enlightenment ideals, found in games what Phillip von Hilgers termed "an epistemic reservoir." Under the influence of the printing press, at this point firmly entrenched in the European intellectual scene, Enlightenment thinkers began advancing new ideas on the role of the self and individualism, the political contract between subject and ruler, and the growing presence of an educated, professional class that could aid governments in administrating grand conceptions of civil society. It was the beginning of the modern era when new problems and possibilities emerged, demanding new answers and configurations. Yet before we can address how board games helped provide these new answers and conceptions, we must first establish definitions on the types of epistemic reservoirs games could provide.

Broadly defined, there are two states of knowledge games produce; dualist and augmented. Because dualist conceptions claim to constitute their own epistemic field of knowledge, the execution or embodiment of those conceptions, even while governed by rules of their own operation, nonetheless remain isolated from reality. The real question for dualist conceptions lies in their points of contact with reality, the knowledge handoffs that remain discreet and fire-walled yet facilitate interaction between the realms. In contrast augmented conceptions are intermeshed with reality, thus shifting the question away from knowledge handoffs specifically, although they are still vital, and towards the type of knowledge those handoffs facilitate. Nor is it a question of measuring the degree to which augmented knowledge intermeshes with reality, be it a scanner densely or thinly as it were. When analyzing the types of augmented knowledge produced, qualifiers like de jure and de facto help demarcate the influence these constructs held in connection to the lived experience.

What does it mean to say there is a difference between de jure and de facto augmented knowledge? De jure knowledge is that which claims an epistemological linkage to truth, but also on grounds not fully realized due to either the structuring of the augmented construct or the normative reality surrounding the construct's operation, which can obscure the veracity of the linkage produced. De facto knowledge is a smooth elaboration of the rough form hewn through de jure means. Not only is the epistemological linkage to truth made stronger and resolute, but the structure of the augmented construct becomes reflective of the normative reality surrounding its operation, offering a potential for reflection, critique, and occasional prescience. This, in turn, raises a new question; how do games fit into this schematization? Some descriptive examples should help clarify the terms at hand.

Although it is a broad statement to make, for the terms of this essay it can be said that board games up to the 17th century embraced dualist modes of knowledge production. Several factors necessitated this design aesthetic. Without widespread literacy or available printing technology, it was difficult to create a board game of great complexity and homogeneity at the level required for augmented knowledge production. Extreme abstraction and simple, geometric design overcame these obstacles at the cost of distancing the game from the lived reality of its players.

|

| The Tablut Game Board |

Tablut is a good example of a board game constructed in this dualist aesthetic. First recorded by Carl Linnaeus during his travels through Swedish Lapland in the 18th century, Tablut is a derivative of the Tafl family of board games whose pedigree stretches back hundreds of years. Tafl games are asymmetric, depicting a smaller, defensive force against a larger, offensive force closing in on the center of the board and trying to capture a 'king' piece. Linnaeus recorded that Tablut pitted the lighter colored 'Swede' pieces against the darker colored 'Muscovite' pieces. The goal of the 'Swede' player was to move the King piece to specific portions on the edge of the game board, while the 'Muscovite' player must surround the King piece with four pieces of their own. It is an interesting game that hints at a deeper cultural narrative, yet playing the game yields knowledge related just to the game itself. A player may glean strategic considerations applicable, at some translative cost, to situations outside the ludic reality of Tablut, but often the greater balance of knowledge accrued informs only the ludic reality of Tablut. To put it simply, playing Tablut mostly makes you a better Tablut player.

Other games, like Chess or Go, fall into the same dualist category occupied by Tablut. They represented cultural influences or narratives that made up the lived reality of their creators and initial players alike, but the telescopic perspective employed kept these games from directly intermeshing with this same lived reality. This is not to say that dualist games are inferior to augmented ones or that augmented games supplant dualist designs, only that dualist games hold at their core the notion of distinct epistemologies demarcating the ludic from the real. These two worlds interact through knowledge handoffs, such as the notion of cunning gameplay being equated to raw skill or the way Go interacts with military philosophy through design mechanics, but these linkages are often described as ephemeral and tangential to the experience of the real. Rather than viewed as detraction, the 'escapist' elements of dualist games often provide a compelling factor for their sustained longevity through the centuries.

Augmented games, by comparison, are relatively youthful in presence, the foundations for their emergence secured only with the arrival of both baroque and enlightenment ideals circulating through Europe, beginning in the 17th century. Particularly in Northern Europe, where Reformation theology promoted greater individualistic and rationalistic intellectual pursuits, thinkers advanced configurative tools for analyzing the surrounding reality, rapidly divulging its long kept secrets to philosophers and natural scientists alike, in new and innovative ways. Mathematical breakthroughs in calculus, statistics, and probability readily lent themselves to novel, penetrating analyses of society that opened up such fields as demography and mortality studies. Baroque influences, focused in Spain but reaching out to other Catholic and even non-Catholic states, brought about a divergent ideal that the spiritual, then under assault by humanistic inquiries, was not illusionary or explained away by rationalism, but rather that the spirit could imbue art, architecture, theatre, and more- you may recall from Schorke's essay discussed above that Austrian aesthetic culture of the 19th century pursued baroque configurations embodied in the performative arts- with an inspirational feeling that drew upon the soul-nourishing wellspring of divine grace for both execution and effect. Although the Baroque was initially fostered by the Catholic Church as a means to combat Reformation influence, in part, through an all out aesthetic assault on the senses, the larger philosophical implications surrounding this unleashing of the divine into the unified field of art produced reverberations felt even to this day. Within this heady cauldron of 'grace and the word' stewed the late 17th and early 18th centuries, their complexity first revealing, then demanding, new forms of governance and new ways of viewing populations. These challenges, in turn, required new analytical models and techniques wholly different from those utilized in the past.

|

| Leibniz |

Enter Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. His work found in games a new potential for knowledge, elevating design aesthetics to an augmented level that, for the first time, granted ludic knowledge a credible link to epistemologies feeding the real, lived experience. He managed to accomplish this philosophical feat through careful blending of both enlightenment and baroque ideals. "Men are never more ingenious than in inventing games," wrote Leibniz in 1715, the statement revealing his supreme affection for ludic creation as an exemplar of enlightenment reason embodied in perspective. Yet, as Deleuze reminds us in The Fold,

"For Leibniz…perspectivism amounts to a relativism, but not the relativism we take for granted. It is not a variation of truth according to subject, but the condition in which the truth of a variation appears to the subject. This is the very idea of Baroque perspective."

A game does not reveal a singular truth through play- it reveals the possible range of truths that could have been and might still be. Leibniz himself acknowledged this idea when discussing how newly created 'war games' of the 17th century could allow the replaying of historic battles:

"…one could represent with certain game pieces certain battles and skirmishes, also the position of the weapons and the lay of the land, both at one's discretion and form history…thereby one would often find what other missed and how we could gain wisdom from the losses of our forerunners."

Again, it was the 17th century which first saw games assume positions as augmented knowledge producers, free from the intrinsic separateness embodied in dualist designs. Philip von Hilgers notes as much with his discussion on the transformation of games during this period in his book, War Games: A History of War on Paper:

"In the games of the seventeenth century, representational forms suffer a breach. In their place, semiotic operations are promoted to the prosperous switch point of knowledge. Games are themselves released from purposelessness. They can change at any point into a teleological model entrusted even with foregrounding underpinnings of the state: Fortifications and theatre buildings, firearms and fireworks, or mathematics and games are skills are skills that find representation in the very same books."

The rise of Enlightenment inspired rationalism and Baroque perspective went hand in hand with the rise of games as augmented knowledge producers because not only did new techniques engendered by these philosophical traditions allow for greater simulative capability, but they also allowed for players and designers alike to experiment with notions of time and space in ways that dualist games could not achieve. As board game design began to move away from telescopic perspective, the prospect for analyzing time and space as discreet units became possible and it is perhaps this characteristic, above all others, that distinguishes the augmented from the dualist in terms of ludic experience creating applicable knowledge. Military affairs, discussed in greater depth in the second portion of this essay, were natural extensions for utilization of this new, augmented ludic knowledge described by Leibniz, but augmented games of the 17th century also sought to inform social matters then being hotly debated in royal courts and town halls around Europe. In the years just previous to the rise of Leibniz, a revolutionary board game created by Christoph Weickmann, a patrician of the German state of Ulm, paved the way for board games to become de jure knowledge producers for the social sphere.

|

| 'Great King's Game' Title Page |

Titled the 'Newly Invented Great King's Game', Weickmann's design came to him in a dream partially inspired, no doubt, by the lengthy games of chess played the day previous to his nocturnal sojourn. Over the span of two written volumes, Weickmann elaborated the rules, boards, pieces and justifications used to inform the grandiose design. What we would term the 'rules of play' only constituted a sixth of the total writings devoted to the Game's explanation. Philip von Hilgers notes that the majority of Weickmann's prose centered on sixty 'observations' of baroque prolixity, using historical examples and authoritative, military missives in order to provide reasoning behind the combat and movement allowed in the game. Instead of the sixteen figures found in Chess, the 'Great King's Game' provided players with thirty pieces and fourteen different types of movement, all of which are depicted on the game board whose graphical representation shifts away from the traditional square and into varied configurations depending on the number of players engaged.

Weickmann's 'game' was not altogether a novel epiphany, as previous work by Augustus the Younger (penned under his pseudonym Gustavus Selenus), published in 1616, described the play of chess as an informative activity that could advise King's of the 17th century on issues of governance and military affairs. However, Weickmann's game differed from Selenus' work in several important respects. Not only were there more pieces and extensions/alterations of the traditional Chessboard, but there was also an elaboration of represented roles for the pieces (the Marshall, the Chancellor, the Soldier, among others) that mimicked the, then, growing presence of a professional service class among the courts of Europe. Even though Weickmann, who dedicated his game to Augustus, clearly was influenced by the nobleman's idea that chess could inform real life situations, he brought more immediacy and realization of this idea through lengthy 'justifications' of his design, sourced in contemporary and ancient observations, in addition to providing rule mechanics that allowed pieces to become promoted via capture of an enemy figure.

|

| Various pieces found in Weickmann's game |

On face, these differences amounted to a more complicated version of chess. But the intent of the game reveals a deeper level to this novel amalgamation of (then) contemporary modernity. Weickmann stated in his written manuals that, "through this game a high-ranking person could thus investigate and interrogate all distinguished officials' temperaments easily and without any effort, which cannot happen so easily." Playing the 'Great King's Game' could inform more than strategic considerations- it could reveal, to the careful observer, the personal workings and mettle of a potential candidate for service in the name of the King. As von Hilgers notes, this mirrored the reality facing rulers just after the Thirty Years War, when absolutism began its inevitable decline and more egalitarian models of representation and governance came to the fore. The rise of a civil service, or at least a professional middle class, brought potentially untested and unknown (read: non-noble) candidates to greater positions of power. It was therefore a pressing need which Weickmann's game served to address; with psychological techniques only nascent in their development, the board game remained one of the few constructs capable of both time compression and augmented knowledge production relevant to the lived experience.

At a stroke, the 'Great King's Game' surmounted the previous difficulties of dualist designs and brought the ludic experience of play to the level of de jure augmentation. One didn't play with complete abstraction, because the pieces involved found a basis in the lived experience of Weickmann's surroundings. Rules of play weren't arbitrary, because they were based on an empirical data set that, at least, provided a reasonable justification for how the game should operate and the standards of verisimilitude it's results should produce. The ludic experience of play was not ephemeral or tangential; it was indicative of a trend, moving forward, that found games providing clear, informative linkages to the real. Playing the 'Great King's Game' didn't make a more skilled and cunning player, it made the player a more skilled and cunning observer of the social and political questions then in vogue. Playing the game both filled and drew upon the epistemic reservoir created by its de jure augmented presence. Whereas one would previously need years of evaluation to determine the worth of an individual, here a potential candidate could be screened and evaluated through a construct that compressed those once required years into a few hours or days.

Despite all the advantages Weickmann's game presented, it still could not be classified as a de facto knowledge producer. Social norms related to conceptions of sovereign power and the still pervasive influence of landed nobility, even in an era where new governmental configurations were debated, prohibited the game from truly intermeshing with the surrounding reality of its operation. There is also the question of its form; a two volume, one-off print could hardly spread beyond the limited locale of its production. Thus, from a social and constructural standpoint, the 'Great King's Game' might have been an amusing, if not useful, toy for those in power, but it could not meaningfully present challenges or critiques to the system it was designed to inform.

Although Weickmann's game could not be called a resounding success, the design ideas and gameplay having never caught on, it did provide fertile ground for Enlightenment precepts then emerging in Europe. Combining several emerging knowledge fields- statistics, military science, psychology- the game could easily be seen as a prime exemplar of the new potentials these advances would collectively make. The rationality behind it's operation, that 'baroque prolixity' which promised verification in addition to evaluative capacity, demonstrated that such abstract reasoning could build towards a greater understanding of the present and potentiality of the future. It is here- in the birth of the augmented board game- that the seeds of conflict between Baroque and Enlightenment ideals, the battle between Grace and the Word, were sown. For while games opened the door for rational evaluation, they did so at the mistaken cost of believing in the supremacy of written sources and the progressive spirit of the age. Mechanistic operations governing the whole of reality were assumed to be perfectly rational and perfectly understandable, thus giving Weickmann an unparalleled confidence in the predictive nature of his game even while the baroque understanding and perspective offered in its design hinted towards an understanding that went against the grain of rationality.

Leibniz begin to uncover this ideal through his work on probability and elaboration of the monad, yet it would take an additional two hundred years before authors like Herman Hesse and Robert Coover could demonstrate a way for games to escape this de jure designation and enter into full blown de facto augmented knowledge production. Of course, while Weickmann's game didn't take hold in social spheres, the fact that a board game could play with discreet units of time and produce augmented knowledge found greater acceptance for militaristic affairs. In the next portion of this essay, The Limits of Dualism, I will explore the implications for military assimilation of augmented board game knowledge while also pondering the ultimate failure of Enlightenment based dualist assumptions found at the heart of Schorske's Austrian aesthetic conflict found in 'Grace and the Word.'