To paraphrase that self-deprecating comedian, Rodney Dangerfield: board games can't get no respect.

At least, that's what the recent MoMa announcement on acquiring video games for its collection would lead you believe.

On the 29th of November, the MoMa 'Inside/Out' blog announced that 14 video games, the likes of which included Pac-Man, Myst, Tetris, Portal, and EVE Online, were acquired as a seedbed for a "new category of artworks…that we hope will grow in the future." As of March 2013, visitors to the Philip Johnson Galleries will be able to view, and in some cases actually play, the acquired games and, hopefully, marvel at their construction as exemplars of 'interaction design'.

Paola Antonelli, senior curator in the Department of Architecture and Design, told the Wall Street Journal's 'Speakeasy' blog that, "…interaction design is a discipline that was born in the 1980s...and it has to do with our interaction and our experience of digital artifacts. So, it is the screens of ATM machines. It is the screens of computers. And it’s also video games."

And here we get to the heart of the matter. MoMa didn't acquire these video games as 'works of art', although the 'Inside/Out' blog and Ms. Antonelli clearly feel they could be huddled under this category. They, instead, fall under the category of 'interaction design', standing alongside other MoMa stalwarts ranging from, "posters to chairs to cars to fonts." It's not so much the form that is exciting to MoMa- it's the 'experience' these video games evoke, the way they pair technological constraints and programing code to create a ludic range of emotion through play.

Yet, while I applaud MoMa's decision to incorporate these important cultural artifacts into their museum space and exploration, I cannot help but ask: Where are the board games? Looking over the criteria highlighted by both the 'Inside/Out' blog and Ms. Antonelli's comments, there would appear to be generous room for allowing video game's analog brethren a space in MoMa's hallowed halls. Take this quote, again from Ms. Antonelli:

"Video games are really full-formed examples of behavioral design, experiential design. You need to have a sense of space and a knowledge of architecture, whether it's instinctive or really formed. It's about aesthetics, of course. It's about all of these different categories that come together in a design artifact."

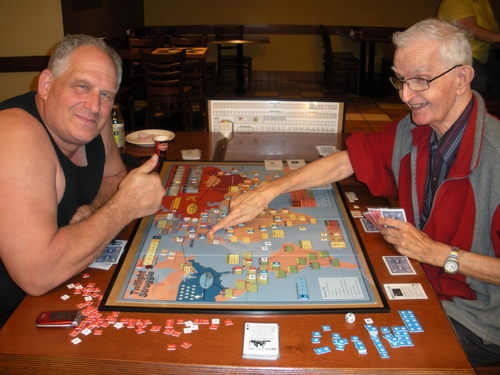

Or, from another angle, look at the four 'central interaction design traits' highlighted at the 'Inside/Out' blog; Behavior, Aesthetics, Space, and Time. Nothing about these four traits would appear to disqualify board games from being included. In fact, one of my own essays over at The New Inquiry, 'No Accidents, Comrade', specifically addressed both Antonelli's comments and the four traits mentioned above with regards to the popular Cold War board game Twilight Struggle. No, it's not that board games aren't capable of meeting the rigorous standards of MoMa exhibits- they clearly can- but, rather, the conspicuous absence of board games hints towards a larger issue at stake.

From my perspective, what we have here is a clear antagonism between the coding mystique and the banality of cardboard.

What do I mean by 'the coding mystique'? It's simple- coding is one specialized skill that few of us can claim to have mastered, yet our lives are dependent on the operation of code increasingly found in everyday objects. It's invisible, moving behind the scenes of our favorite apps or devices that bring us news, or connections, or opportunities to expand our horizons, yet few of us actually understand how code works or how deeply it has already imbedded itself into our daily lives. Code radiates power (when properly compiled) that is awesome in both senses of the word. We are literally struck with wonderment in the presence of superb code (like iOS on the iPad), but also a sense of dread at the implications code projects (like the algorithms powering Facebook, or the use of cookies to track your online behavior for marketers).

Video games are another example of the 'coding mystique'. In completed form, players never see the presence of code in video games, they only 'experience' the effects generated by that code. I still remember the first time I played 'Grand Theft Auto 3'- it was an incredible open-world experience few games, up to that point, could achieve. However, I never saw a single line of code while playing. I never engaged in 'modding' or other activities that might have exposed the underbelly of the game's internal workings embedded in code. The 'black box' encapsulating the code of GTA 3 never once surfaced during play and, thus, the 'coding mystique' held total control of my gaming experience without ever once revealing its tendril-like grip on my brain and my body.

Compare this to the banality of cardboard.

Manual games have no 'black boxing', the code underlying their operation located in plain sight with regards to the printed rules. Anyone who can read can reasonably play a board game. Beyond this, anyone who can read and write can *modify* a board game with relative ease. Without obfuscation, there simply cannot be any 'mystique' associated with board games. Hence, the banality of cardboard.

Despite this banality, board games still possess all the qualities listed above by Ms. Antonelli and the 'Inside/Out' blog. Board games are, at their core, experiential designs. They create a ludic space, just like video games, based on a designed architecture that plays with both space and time through the use of mechanics and aesthetics. One difference board games possess is that the imagery created is wholly dependent on the player. They create the narrative through play (especially in solitaire games), even if this narrative is guided through design. Video games, in contrast, force narrative interpretation upon the player. Sequencing of displayed imagery, while tied to player interaction via controller, is nonetheless fait accompli. The code already contains every potentiality, every possible outcome that the player could force. You can't 'cheat', unless the code says you can, meaning that there is no way to metaphysically break the boundaries of the video game universe. And even if the game does allow cheats, these are still bound to the rules circumscribed by code's operation.

Board games, despite their banality, can actually survive cheating (either on purpose, or by mistake) undertaken by the player. The entire narrative assemblage process escapes pre-deterministic outcomes because the player creates the meaning- a process limited only by imagination and not the boundaries of code. Cardboard appears banal because we give the cardboard meaning through play. Video games have mystique because the code gives meaning to us through play.

There are other issues too, like the nature of the museum space. Here again is Ms. Antonelli:

"We’re not going to have the arcade cabinets. We are going to acquire the hardware, because it’s important to have it, but at least at first, we’re not going to show it. We’re going to have screens that are as close as possible in size to the original screens, and of course, we’re going to have the controllers. The controllers are very important, but my dream, and I don’t know yet if I’ll be able to do it, is to have controllers that are all made with the same plastic in the same color. Of course, they have whatever joysticks or buttons they need to have. It’s important to have those. But I would like to kind of make everything that has to do with the hardware as abstract as possible, so that people can concentrate on the interaction. I want to create that distance, so that people can really understand what we mean by these games being masterpieces of interaction design."

While MoMa is keen on the act of preservation, the goal being to fully document not just the code and materials of video games but also the process involved in making the code, Antonelli's quote above details the type of exhibit MoMa wants to create. Hardware is absent. Controllers, if able, would be all alike, indistinguishable from one another so as not to interfere with concentration on 'interaction'. In short, the player would be presented only with the 'experience' as enabled by the code.

Board games could never submit to such a configuration in an exhibit. MoMa can easily package and present video games to fit a particular point of view. Board games, however, are not so easily molded. If the goal is to have the viewer focus on the 'interaction' and achieve 'experience', then the only way to do this with a board game is to actually play it. One has to shuffle the cards, or distribute the tokens and chits, to get a sense of the 'experience'. Video games can be put on 'demo' mode, and even a 'static' like presentation will still contain vibrant, moving imagery. Not so with board games. As a display, they would appear inert and without life. As an exhibit designed to foster interaction and experience, board games would require hands-on interaction with other humans, other players, for the 'experience' and 'interaction' to take hold. The 'distance' that Ms. Antonelli wants to foster with the video game exhibit would become compromised in a board game setting, as interaction with the game and other opponents provides player agency in determining meaning that, by necessity, obviates the 'space' needed for a traditional museum exhibit.

While discussing this topic on Twitter, Felan Parker (@Felantron) made another good point worth mentioning; while (some) video games pursue "art status or alignment with established art forms," board games have largely eschewed this goal. There are some notable exceptions, Brenda Romero's 'Train' being a particularly good example. And it should also be noted that MoMa isn't classifying their video games as 'art', but rather as objects of superb design. Still, the fact that video games aspire to art status is wholly indicative of the 'coding mystique' they possess. Cardboard, a product of more humble intent, cloaks itself in a banality that betrays its larger purpose and meaning.

Board games might get no respect, but they certainly should.