Specifically, Patrick advocates that the US must recognize that it no longer has the clout to effectively mandate unilateral change and must look to find engagement with the world through multilateral institutions, while at the same time ensuring, via our clout and unilateralism, that 'emerging powers' adhere to rules and standards required of the Western political order. (this includes countries such as China, India, Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia, South Africa, etc...) Thus, to quote Patrick, "the United States must link any extension of international status, voice, and weight of the emerging powers to their concrete contributions to world stability," (Foreign Affairs, 52) because many of these emerging powers "often oppose the political ground rules of the inherited Western liberal order..." (Foreign Affairs, 44) What Patrick fails to take into account is that the Western liberal order discussed above is not a monolithic institution as much as it is a specific configuration of liberalism developed in the United States that incorporates elements of a 'similarity' discourse fused with an unfailing belief in the market as a divine arbiter of large spheres of human activity. I want to take some time to look at how this conception of liberalism took hold in America, how Imperial Russia's experience with liberalistic values and institutions in the 19th-20th centuries informs this inquiry, and, finally, how this analysis demonstrates that Patrick's essay flounders on contradictory goals.

Two Aspects of American Liberalism

I do not want to give the impression that the interweaving of ideas that is American Liberalism can be explained solely by two influences when serious debate on the subject could easily throw out dozens more. What can be said with confidence though is that the complex beast of American Liberalism came to dominate, or at least seriously sway, the practices of other Western nations during the period of the Cold War when ideological battles between capitalism and communism waged supreme. Since the end of the Cold War and especially in light of the recent financial meltdown led by faulty American debt instruments, American hegemony and thus American Liberalism have declined in their rhetorical power to shepherd the 'emerging powers' towards their ideological viewpoint. This is the crisis Patrick highlights in his essay and it is my belief that the 'emerging powers' are not so quick to take up the 'Western liberal order' because they find elements within to be less appealing than they once were.

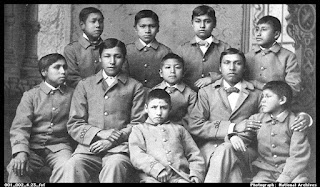

To begin, American Liberalism is built upon the idea of 'similarity', a concept I am borrowing from Philip Deloria in his work Indians in Unexpected Places. Deloria convincingly argues that whites developed changes to language use and conception in order to accomodate the shifting phases of Indian-White relations; from fear to surround to outbreak to last stand to assimilation and finally invisibility. When Whites began to assimilate the native population, they did so with a goal of producing 'similarity' and not fully accepted citizens. Native children that attended Carlisle or Haskel were transformed into peoples 'similar' to the larger White society, but not 'exactly' like the larger White society. This attitude infused itself within the core understanding of American Liberalism, finding later expression in the idea that spreading American style democracy and ideals around the globe would instil 'similar' governments and societal configurations that, while not exactly like America, could co-exist peacefully with America. This was the central idea behind such efforts like the Peace Corps or US AID, even the Marshall Plan- believing we had the best way of life to offer, many American foreign policy efforts of the 20th and early 21st century specifically endorsed this idea of promoting 'similarity' of American Liberalism around the globe.

|

| Spreading 'Similarity' via Ad*Access |

"First, the generalization of the economic form of the market beyond monetary exchanges functions in American neo-liberalism as a principle of intelligibility and a principle of decipherment of social relationships and individual behavior. This means that analysis in terms of the market economy...can function as a schema which is applicable to non-economic domains. And, thanks to this analytical schema or grid of intelligibility, it will be possible to reveal in non-economic processes, relations, and behavior a number of intelligible relations which otherwise would not have appeared as such- a sort of economic analysis of the non-economic." (Birth of the Biopolitics, 243)Here is a small clip from the PBS documentary Commanding Heights on the Chicago School and its influence on American economic culture.

Yet, in the wake of the financial meltdown of 2008-2009, faith in the 'free' markets is mildly tenable at best around the world, with some non-conformist players like China demonstrating the power of strong central control in regulating the extreme fluctuations of the market. The 'emerging powers', thanks in part to the communication technologies discussed in more detail in the essays of Schmidt, Jared and Cohen, now have the ability to pick and choose from among the state/society configurations debated about within the aether of the internet and this in turn is bringing about a shift in relations many nations have with the United States, as noted by Patrick in his essay. American Liberalism, with its emphasis on 'similarity' and the arbiter 'market', quite simply is not the hot product it once was.

The Russian Example

|

Peasants from Korobovo Village- from |

The Mobility of Liberalism

Underlying both the American and Russian reconfigurations of Liberalism, as well as the challenge by Patrick's 'emerging powers' to the current 'Western liberal order', is a transformational quality of ideas that I term 'Mobility' by which ideas/information circulates, becomes 'certified', undergoes mutation via 'certification' and application before being circulated again, repeating the process.

|

| via Steve Jurvetson- Genetic Mutation in Y Chromosome tracks Familial Movement |

Technology and Circulation

Circulation and the mutation of Liberalism highlights the error of Patrick's argument, as he contends that the 'Western liberal order' is the gold standard of global stewardship and prerequisite of admittance to its ranks, when, as we look to the essays of Schmidt, Jared and Cohen, the rise of mass communications technologies makes such monolithic ideological dispersion and acceptance claims difficult to muster as new configurations of Liberalistic models will constantly, and with increasing speed, rise to challenge older models. Schmidt and Cohen in Digital Disruption point out that China, who uses perhaps the most sophisticated censorship techniques with regards to Internet access, is attempting to give this controlled model of Liberalistic Internet more credibility by circulating it among the varied governments, some 'emerging powers', in order to give the model more credibility on the world stage. In other 'partially connected states' such as Cote d'Ivoire, Pakistan and Guinea, Schmidt and Cohen discuss how,

"Today's activists are local and yet highly global: they import tools from abroad for their own purposes while exporting their own ideas." (Foreign Affairs, 82)In effect the increased access to information and desire to use global ideas in a configuration suited to local needs lowers the previous 'certification' level of these ideas, permitting increasing diasporas to not only access them but re-circulate them in a 'mutated' form, again globally accessible and capable via circulation of being 'mutated' again. As noted in Digital Disruption, hyper-connected societies such as Israel, Finland and Sweeden, who invest a significant portion of their GDP into communications research and development stand to reap the benefits of this increased information circulation potential. While Schmidt and Cohen acknowledge that digital communicaiton technologies can be abused by authoritarian regimes, they tend to side on the hopeful expression of more Liberal values citing the potential of 'flash mobs' organized by text, tweet, or social networking.

Ian Bremmers's essay, Democracy in Cyberspace, takes a much more negative view on the potential of communication technology to facilitate the spread of liberal ideals and models. While noting that such technology is 'value neutral', having only the moral characteristics of the users, Bremmer is quick to note that such neutrality also proscribes the belief that use of communications tools- many created in America- will lead to embracing liberal democratic ideals. Instead what we are seeing is the enactment of 'feedback loops' in which world politics is fundamentally changing the internet. Bremmer points out how threats of cyberterrorism forced governments to reconsider their telecommunications as critical infrastructure, which could lead to the integration of communication technology providers increasingly within the realms of the military-industrial complex fraught with secrecy and security. Below is President Eisenhower and his famous speech on the Military-Industrial Complex.

Conclusion

Bremmer, along with Schmidt and Cohen, demonstrate how communication technology is facilitating the circulation of knowledge among diverse societies and governmental regimes, a process that allows once dominantly held views inherent in the 'Western liberal order' and American Liberalism to be questioned and possibly replaced with local configurations more suited to local needs. These configurations may not succeed, just as Imperial Russia fell to the rigors of World War I due, in some part, to their inability to secure the allegiance of their diverse population with a definition of citizenry defined in Great Russian ethnic terms. Yet they will exist, they will be studied, and they will be spread, spurring the development of even greater mutations producing truly varied configurations of ideals like Liberalism.

While Patrick is mostly correct in his analysis of American needs to engage in multilateralism, his insistence on preservation of the post-World War II liberal order as a condition and qualifier for acceptance of 'emerging powers' into the global order ignores the fact that American Liberalism is far less attractive than it once was and that these rising nations are more than capable, using communication technologies, of reconfiguring Liberalism for their own needs.

No comments:

Post a Comment